Theory for urban environment design 17 Dec. 2014

都市環境設計論 2014年12月17日

Prof. Mowla gave a special lecture for EEP on "Deciphering the Evolutionary Form of Urban Dhaka". As this lecture is a class for "Theory for urban environment design" of Dept. of environmental design, school of design, many students attended the lecture. Students' comments are basically very positive, though they have some language barrier.

Time: 16:40-18:10, Venue: Room524 (2nd floor of Bldg.5) Ohashi campus.

モウラ先生のEEP特別講義「ダッカの都市形態進化の解読」が行われました。この講義は芸術工学部環境設計学科の「都市環境設計論」の一部であったので,多数の学生諸君が出席しました。英語の講義ということで不慣れな面もあったはずですが,授業後に書いてもらったコメントは概ね前向きなものでした。

時刻: 16:40~18:10, 場所: 524教室(大橋キャンパス5号館2階)

Deciphering the Evolutionary Form of Urban Dhaka

by

Qazi Azizul Mowla, PhD,FIAB

Visiting Professor, Faculty of Design,

Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan

&

Professor, Faculty of Architecture and Planning,

Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Synopsis of the Paper

Dhaka (the capital city of Bangladesh) epitomizes a long history of urbanization influenced by various cultural phases, sometimes hostile to its natural process of evolution.

Water bodies and rivers have historically played an important role in the development of Dhaka. The Dhaka conurbation, as a meeting point of major riverine routes, served as an outlet to a vast hinterland. The matrix was a constellation of villages, where for different reasons at different times one village or another became the dominant political centre to acquire the status of a City (Ganjor hat-market place is synonymous to indigenous city). Dhaka has grown from a small settlement within the confines of the river Buriganga and the Dholai Khalto a sprawling metropolis. Water channels (Khal) played an important role in the indigenous city life. Most of these Khalslie east west which used to serve, besides other needs, an important purpose of intra-city communication. The prong of flood free terrace averages about 6 km in width and the growth has generally been northwards from the old nucleus along the Buriganga river.

Local culture and the way of life had always been a unique modifier to absorb or adapt, which is new, in its folds. A series of superimposed or juxtaposed layers of interventions due to these phases, sometimes beyond recognition, when unfolded, reveal an archetype deep beneath. This archetype shows clues to a hidden order that gives a distinctive texture to indigenous settlement morphology. In order to understand the contemporary urban form of Dhaka or to predict its future, it is essential to understand the process and context of its evolution. Therefore, the process of the spatial evolution of Dhaka is the subject of analysis and synthesis, in this presentation, to decypher the archetype forming the contemporary form and morphology of urban Dhaka.

Growth of Dhaka over last 400 years

At its peak at about 1660 to 1690, Dhaka city with its suburbs had a population of about 900,000. During that time the city proper stretched seven to ten miles along the river Buriganga and up to two and half miles inland. The suburbs extended from Buriganga to Tongi bridge, fifteen miles to the north, and from Mirpur-Jafarabad on the west to some ten miles to the east to Postogola. In 1765 the city core had an estimated population of 450,000 and stretched nearly four miles along the river and two and half miles deep, signifying a decline of the city. Two principal streets crossed each other at Chouk, one east west running parallel to the river and another from the river to the defence outpost in the north to Tongi through Tejgaon. The city could be approached by river from the east, hence a series of forts were built on the way and two forts were built on either sides of Dholai Khalin 16th century, at the entry point of the city. The city was well protected by a natural system of rivers and a network of canals and low lands. A formal gate on the north marked the limits of the city core. Beyond the gate were the royal pleasure gardens and suburb settlements. From medieval times some external forces played a pivotal role in the shaping of the contemporary pattern of growth and pattern of Bangladeshi settlements particularly of Dhaka

Transformation of the Social Structure into Physical Form

The preparation of food, its consumption, ritual observations, sanitation practices and caste belief and practices governed all systems of social behaviour. The nucleuses of social structure were household (ghar) and homestead (bari). Neighbourhood or mahalla (also called para) were mainly composed of family lineage (paribar). The social structure was similar to contemporary rural structure in Bangladesh. Physical manifestation of family level out door activities gave rise to uthanor courtyard house and galiesor lane/by lanes. Male head of the household occupied dominant and better locations in the settlement.

Oldest pattern of settlement in Dhaka

Geo-climate of the place and Societal norms greatly influenced morphology of the oldest pattern of settlements in Dhaka. The conglomeration of Hindu names of localities in the Banglabazar area of the city viz. Jaluanagar, Banianagar, Goalnagar, Tantibazar, Shankharibazar, Patuatuli, Kamartuli and so on, clearly bear testimony to their early existence. The Dholai Khal formed the northeastern boundary of this urban entity. These settlements of professional groups were a sort of densified villages. Banglabazar, which was the centre and main shopping area before the Mughals, yielded its supremacy to Choukin Mughal period.

Evolution of Urban Space in Dhaka from Indigenous Context

Apart from east-west and north-south road with their centre at Chouk, the remainder of the city streets tended to be quite irregular in direction, length and width. A mélange of convoluted streets, cul-de-sacs, alleys and byways gives access to residences and other uses. Gates or doorways open to private holdings and courtyards (uthan) making the high density more tolerable. This was an organic growth following the topography - the basic urban unit was a mahalla: a squeezed counterpart of the indigenous village. The mahallas were more or less self-contained as far as daily necessities of life is concerned. Chouk was the city centre with main administrative and commercial power base (fort, bazar, ghat etc.) located around it. The roads connecting the Chouk with specializedmahallas formed the specialized shopping streets.

Settlement and Urban form with the community space as the nucleus

Fundamentally there were two types of mahallas, the Amiri (gentry)Mahallas and the Service Mahallas. Most of the mahallas were self-contained in terms of school, bazar, mosque/temple and sometimes orphanage. In social terms a mahallawas and is a close-knit community, often homogeneous and identified by common occupation, lineage, religion or geographical origin of the people, such as Tikatuli, Armanitola, Patuatoli etc.

The upper crust of Mughal society preferred the western part (e.g. Bakshi Bazar and Dewan Bazar area) of the city, possibly as a precaution from probable attacks coming from the east. The first line of defence was the older indigenous settlements in the east. The rich but non-official Mughal citizen Mahallaswere located between Old Fort and indigenous caste and craft settlements - Becharam Dewri, Aga Sadeque Dewri, Ali Naqi Dewri and Amanat Khan Dewri are some of these mahallas. These were popularly known as Amiri Mahalla. At some distance from the urban core, were the gardens and houses maintained by Mughal nobles and gentry. MahallaSujatpur and MahallaChistian at the north housed many garden houses. Other similar areas were Hazari Bagh, Qazir Bagh, Lalbagh, Bagh Chand Khan, Bagh Hossinuddin, Bagh Musa Khan, Rajar Bagh, Momin Bagh, Aram Bagh and the main one the Bag-e-Badshahi

The services zone, an important aspect of an indigenous city's economic life, housed small and cottage industries. Both in the pre-Mughal and the Mughal era, the service zones (mahallas) were located at the periphery of the urban core. This is evident from the location of services mahalla's, falling between two cores, i.e. the Chouk and the Banglabazar, of two different periods. Pheel Khana (elephant stable) and Mahut Toli (elephant keeper's area) together with some of the previously established areas mentioned in previous illustration were Mughal service mahallas.

The beginning of colonial impact

In around 1820, the discomfort of living in the previous rulers quarters prompted them to move to the indigenous core of Banglabazar/Farash ganj area. It was also close to their old factories and new cantonment in the Mill Barrack area. In 1862 Buckland, the Divisional Commissioner, selected a strip of land about 100 meters in width on the west side of the public road leading north from the public square up to Dholai Khal, for the new Civil lines.

By 1866, the courts for the District Judge, Magistrate and Collector and other subordinate offices were built and shifted to new location. The Square, a historic one, in the indigenous period was a place of a periodic market orHat and a community meeting and recreational place. This was perhaps the first formal clubhouse in Dhaka after European pattern. The Company purchased Antagar Maidan, some time at the end of seventeenth century. The old Armenian clubhouse was demolished in 1825 and a new Dhaka Club was built in the same location popularly known as Racket court. However, Dhaka Club was later shifted to the new Civil Station at Ramna beside the racecourse. The abandoned square was developed as an open space and named after Queen Victoria after the establishment of Civil lines and Imperial rule. The road was named Johnson road. This concentration of public and private establishments triggered a whole series of new development in and around this location. Rai Saheb bazar, which came into existence after the European quarters were shifted to the pre-Mughal area, further developed during this time. Private initiatives and subscriptions established many educational institutions in this locality. Dhaka's district administration is still located along Johnson road.

Race Course - First Major impact of European Civilization on Vernacular urban morphology

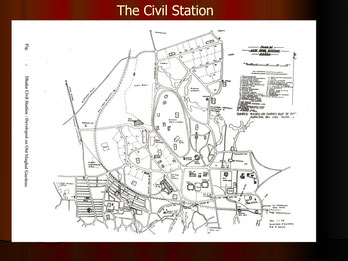

The selection of the site for Dhaka's first railway station at Phulbaria in 1885 marked a lasting impression on Dhaka's urban morphology. The station and the rail line practically demarcated the old (indigenous) and the new (European) developments. Another important development in the morphological evolution of Dhaka around 1905, had been the establishment of a new Civil Station, north of the railway line and around Ramna race-course. The massive development work, with imperial overtones, that began in the civil station with the partition failed to create a desired impact, as partition of Bengal was annulled after just 6 years in 1911.

Evolving Architecture and Urban Design in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a melting pot of many civilizations. Together with the influence of local geo-climate and the indigenous culture, Waves and layers of cross-cultural traits helped formation of a Bangladeshi style.

Evolution of Settlement Morphology in Dhaka: The conceptual typology

Apparently chaotic urban morphology with socio-spatial dimensions provides clues to a hidden order that gives a distinctive texture to Bengal settlement morphology. Some of the notable social norms have transcended from indigenous period to contemporary period. They influenced in producing a set of environmental norms and artefacts using that conceptual framework in subconscious mind. This framework if understood will aid in explaining the link between societal (intangible) values and built-environmental (tangible) artefacts. Other way round, the evaluations of the end product (built environmental artefact) also reveal those human norms and behaviours led to some manifestation in the quality or characteristics of life in terms of comfort or spatial organisation. The framework or relationship that has been identified is expected to be a useful tool for future sustainable urban design in this region. Apparently chaotic urban morphology with socio-spatial dimensions provides clues to a hidden order that gives a distinctive texture to Bengal settlement morphology. Some of the notable social norms have transcended from indigenous period to contemporary period. They influenced in producing a set of environmental norms and artefacts using that conceptual framework in subconscious mind. This framework if understood will aid in explaining the link between societal (intangible) values and built-environmental (tangible) artefacts. Other way round, the evaluations of the end product (built environmental artefact) also reveal those human norms and behaviours led to some manifestation in the quality or characteristics of life in terms of comfort or spatial organisation. The framework or relationship that has been identified is expected to be a useful tool for future sustainable urban design in this region.

Contemporary Morphology of Dhaka

It follows strong zoning laws and hegemony of transport and communication resulting in breakdown of community life. The main drawbacks of fixed zoning regulations are their rigidity, deterministic nature, and lack of response to changing uses and trends and are monotonous. Such regulations also limit the opportunity for achieving environmental quality in the built environment and act as a constraint on creativity resulting in their uniformly repeated spatial elements and patterns resulting in banality. Regulations currently practiced are of the deterministic fixed controls types and include regulations on setbacks, heights, etc. Settlements developing under these regulations have given rise to a number of problems including conflicts with socio-cultural norms, lack of response to the local climate, inefficient land utilization, high development and maintenance costs, negative psychological and health effects and of course sustainability problem.

One of the most important recent lessons learnt from the east (which we forgot) by the western planners and city authorities has been that the ‘local communities’ are the source of all successful planning strategies. Cities of the developing countries including Dhaka are in a planning dilemma as their formal planning is framed on earlier western parameters, while local socio-spatial forces are at odds with that framework. The notion that interventions, if it is to succeed needs to frame its tactics within the local tradition. This demands a clear understanding of the local tradition and foreign implants, and to identify these different strands in the morphology of complex urban areas. A method of explaining design proposals for our physical environment with its socio-cultural context is often needed so that meaning attributed by the designer can be generally understood and publicly debated before implementation commences, and be validated or rejected. With this backdrop in mind this presentation tries to explain the Evolutionary Form of Urban Dhaka.

The flyer for the first EEP lecture.

第1回EEP特別講義のチラシ